Performances conducted by Gustav Mahler with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO):

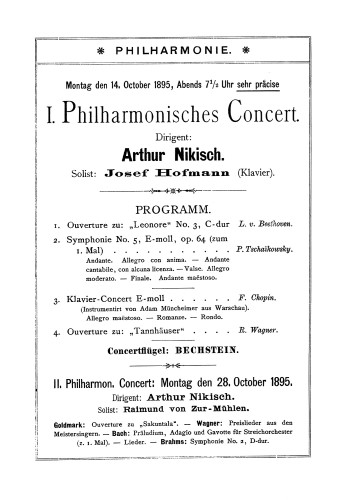

- 1895 Concert Berlin 04-03-1895 – Symphony No. 2 – movement 1, 2 and 3 (Premiere).

- 1895 Concert Berlin 13-12-1895 – Symphony No. 2 (Premiere).

- 1896 Concert Berlin 16-03-1896 – Symphony No. 1, Todtenfeier, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Premiere).

- 1907 Concert Berlin 14-01-1907 – Symphony No. 3.

It started with an act of rebellion: in March 1882 50 members of the ensemble run by the popular musical director Benjamin Bilse refused to sign their new contracts – they found the working conditions too unfavourable: they were to earn hardly more than day labourers. The musicians decided to set up on their own and from then on to work at their own risk. The new orchestra first called itself – referring to their origin – “The Former Bilse’s Ensemble” and they pursued programming concepts similar to those of their former employer: at so-called “Popular Concerts” they usually relied more on entertaining works, while presenting more challenging works and “novelties”, i.e. new pieces by contemporary composers, in their “Symphony Concerts”.

Musical rebels

Back then, Berlin was by no means a prominent European musical capital. Other cities, namely Leipzig and Vienna, set the tone. They had a highly sophisticated concert scene and thus correspondingly imposing concert halls. In contrast, the first performances of the “Philharmonisches Orchester” – as the ensemble was soon called – took place in an open-air restaurant. Starting in the summer of 1882, the orchestra played in the hall of a former roller skating rink in Bernburger Strasse with 2,000 seats. After renovations and improvements, this developed into Berlin’s most important concert hall: the “Philharmonie”.

Struggle for existence

The ambitious young orchestra had high aspirations. The Philharmonic musicians enjoyed their first major successes under conductors like Ludwig von Brenner, Ernst Rudorff and particularly Franz Wüllner. However, their independence harboured financial risks: to be sure, the musicians received administrative support from the start from the enterprising concert agent Hermann Wolff, who organised a subscription series for them and provided them with professional advice. But very soon after their founding the orchestra was buffeted by a difficult crisis that threatened their existence.

1882. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO).

To secure their existence in the long term, they entered into a co-operation with the Royal Music Conservatory, run by the famous violinist Joseph Joachim (1831-1907). The members of the philharmonic orchestra committed to making themselves available to the Conservatory for a certain number of concerts. But Joseph Joachim and Hermann Wolff were personages with different musical worldviews. Rivalry and competition arose between the two of them. Hermann Wolff succeeded in more strongly expanding his influence on the orchestra and in winning over one of the most significant conductors of his time as the principal conductor of his subscription concerts: Hans von Bulow (1830-1894).

In his day Hans von Bülow, who conducted the premiere of Tristan and was known as a brilliant Beethoven and Brahms interpreter, embodied the modern type of conductor: eccentric in his gestures, uncompromising, analytical in his musical work, expressive in his musical results. Not outwardly attractive but possessed of a consummate elegance – he always conducted wearing white kid gloves – he had a compelling, magical charisma. His lordly attitudes and extravagancies were known – and forgiven, because he was one thing above all: an orchestral educator to the nth degree.

1887. Hans von Bulow (1830-1894), Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO).

Beyond uninspired mediocrity

Bülow had already made a first-class orchestra out of the provincial Meiningen court orchestra. Now he hoisted the Berlin Philharmonic, to whom he attested a great artistic intelligence, out of their “uninspired mediocrity” (Allgemeine Musikzeitung) and established standards that formed the basis for the orchestra’s later international fame. Despite his severity and his unrelenting passion for rehearsing, the Philharmoniker felt deeply attached to him as a person. Their collaboration lasted five years, before Bülow, who had suffered from nervous disorders since his childhood, retired from the concert business for health reasons. He died on 12 February 1894.

Intermezzo with Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

His departure left a grievous void in Berlin’s musical life. The concert agent Hermann Wolff tried in vain to engage great conductors like Hans Richter and Felix Mottl; finally, he handed over the musical direction of his subscription concerts to the young Richard Strauss, one of Bülow’s pupils. Strauss, still at the beginning of his career and hoping to succeed Bülow, was not able to attract the Berlin audience into the Philharmonie with his progressive programmes. And Hermann Wolff soon had his eye on another conductor: Arthur Nikisch.

When Hans von Bülow took over the direction of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1887, he was considered among the most important conductors of his time. In contrast, his successor’s name was hardly known: Arthur Nikisch. Born in Hungary, he had just returned from America, where he had conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra for four years. Nikisch, who began his musical career as a violinist in the Viennese Court Opera Orchestra, and was also head of the Leipziger Gewandhausorchester, was possessed of a great sensitivity and intuition and he captured the musicians’ hearts. They let themselves be led by him unquestioningly; they gave their all for him. “It can be asserted unhesitatingly that in a first-class orchestra every single member deserves the designation ‘artist’”, Nikisch once wrote. With this credo he made an essential contribution to the Berlin musicians’ “soloistic” self-image. Through the present day it has remained one of the distinct qualities of the Philharmonic musicians.

Year 1895. Arthur Nikisch (1855-1922), Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO).

Specialised in the aesthetics of sound

The contrast to Bülow could not have been greater: while the former’s interpretations were characterised by intellectual depth and classical rigour, Nikisch, who conducted with quiet and sparing gestures, banked on romantic, sensual colouring and a rhapsodic breadth which felt improvised. He shifted the programmatic emphasis, not only launching German repertoire, but also conducting compositions by Pjotr Iljitsj Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), Franz Liszt (1811-1886), Richard Strauss (1864-1949), Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) – and particularly Anton Bruckner (1824-1896). He was, however, unsympathetic about new compositional ideas from Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Anton Webern, Igor Stravinsky and Maurice Ravel. Unlike Bülow, he was not fanatical about rehearsals; instead, he relied on the intuition of the moment and considered himself re-creator of the works at concerts.

Under his direction the orchestra became increasingly prominent on the international scene; any and all soloists of distinction came to Berlin to perform with the Philharmoniker. But that was not all. Nikisch took many trips with the orchestra and in this way enhanced their international reputation. At the request of Kaiser Wilhelm II, he travelled to Moscow to the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II in 1896 and in the following year captured the hearts of the French audience at a legendary guest concert in Paris – the French had at first harboured a certain resentment towards the Berlin ensemble after losing the Franco-Prussian War. Nikisch conducted the Philharmonic for 27 years. In this time period he conducted more than 600 concerts before dying of influenza in 1922 at the age of 67 – surprising many.

Conductors

- 1882-1887 Ludwig von Brenner (1833-1902)

- 1887-1893 Hans von Bulow (1830-1894)

- 1895-1922 Arthur Nikisch (1855-1922)

- 1922-1945 Wilhelm Furtwangler (1886-1954) (and 1952-1954)

- 1945-1945 Leo Borchard (1899-1945) (1945)

- 1945-1952 Sergiu Celibidache (1912-1996) (ad interim)

- 1954-1989 Herbert von Karajan (1908-1989)

- 1989-2002 Claudio Abbado (1933-2014) (1933-2014)

- 2002-2019 Simon Rattle (1955)

- 2019-0000 Kirill Petrenko (1972)

Also: Berliner Philharmoniker, Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester.