Year 1909. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921). Photo by his friend Gijs Hondius van den Broek (1867-1913). In his study in House Diepenbrock.

- Profession: Composer, teacher Latin, editor of De Nieuwe Gids in Amsterdam. Between 1900 and 1920 he was one of the most famous and celebrated composers in the Netherlands. In his work he mainly occupied himself with vocal music. Remarkable was that Diepenbrock put poetry of his contemporaries on music.

- Residences: Amsterdam, Den Bosch, Laren.

- Relation to Mahler: For 7 years a friend of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). Also friend of Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951), Richard Strauss (1864-1949) and Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951).

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes (Mahler to Diepenbrock):

- Born: 02-09-1862 Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Brothers and sisters:

- Lidwine “Lid” (1859-1933),

- Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) “Fons”,

- Maria “Marie/Mies/Dikmietje” (1864-1931),

- Willem (1866-1925),

- Maurits “Maus” (1869-1943),

- Ludgardis “Lud, Kleinkind, Luit” (1873-1944).

- Married: 08-08-1895 Rosmalen, the Netherlands (without ecclesiastical blessing) to Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939). Diepenbrock family was not present. They met in 1893.

- Died: 05-04-1921 Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 13:00. Aged 58.

- Buried: 09-04-1921 Amsterdam, the Netherlands, RK Begraafplaats (cemetery) Buitenveldert, grave A-I-238.

- Son of Ferdinand Hubert Aloys Diepenbrock and Johanna Josephina Kuijtenbrouwer (1833-1904) (Joanna, Mokje).

- Related to Cardinal Melchior von Diepenbrock, who was his great uncle, as well as to a branch of the family that immigrated to America in 1879.

- House Diepenbrock.

- Gustav Mahler himself in the Netherlands (1903, 1904, 1906, 1909 and 1910)

- 08-03-1906: See Zuiderzee.

- 1912: Friend of Franz Schreker (1878-1934).

Daughters:

- Joanna Luitgardis Huberta Maria Diepenbrock (born 10-08-1905 Amsterdam, died 07-06-1966 Laren) (Jang), 1938-1966 partner of Jan Engelman (born 07-06-1900 Utrecht, died 20-03-1972 Amsterdam). Singer. Joanna and Jan buried: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, RK Begraafplaats Buitenveldert, grave A-I-238 with her parents.

- Dorothea Anne (Thea) Diepenbrock (born 10-07-1907 Amsterdam, died 26-07-1995 Amsterdam) (called Beer). Pianist, married to Matthijs Vermeulen (1888-1967).

Addresses:

- 1862: Rokin, Westereinde and Singel, Amsterdam.

- 1888: Grote Markt, Hotel ‘t Groenhuis, Verwersstraat, Hinthamereinde, Den Bosch.

- 1888-1893: Markt 29 (De Kleine Winst), second floor, Den Bosch. Teacher Latin and Greek at the Gymnasium. Composition ‘Missa in de festo’ (1891).

- 1893: First meeting Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939), House Annastate, Den Bosch.

- 1895: Marriage.

- 1895: Parkweg (now Willemsparkweg), Amsterdam. Rented. With treatment room of Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) (Speech therapist), Alphons was private teacher here. Paul Goekoop gave financial support.

- 1901-1921: Johannes Verhulststraat 89, Amsterdam. House Diepenbrock. Visited by Gustav Mahler (1860-1911).

- 1904: Villa De Hoeve of Saar de Swart (1861-1951). Drift 14, Laren. Holiday visits.

- 1910: Second home in Laren (built 1910): House Diepenbrock “Holtwick”, Drift 45, Laren (near Villa De Hoeve, Drift 14). The construction costs for the “Kleine (small) Diepenbrock villa” in 1910 were fl. 4,400: It was in 1909 that Fons and Elsa could buy a piece of land in Laren to build a summer house there. On the Drift, at the end of the road where De Hoeve stood from Saar and Emilie, a plot of land for sale was available for fl 750. The all in for building and land of fl. 6.000 would pay for itself by letting from home to tourists and the rising market value. Laren was popular with the upper class (which provoked at Fons that ‘the quantum of Jews also increases naturally). Relatively, the investment was far from neutral. A second home gave the couple the space to live separately at times. The cottage would be called Holtwick, after the estate of Fons’ great-grandfather in Westphalia. It had to be under roof in the spring of 1910.

Year 1888. House ‘De Kleine Winst’, Markt 29, Den Bosch. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) lived here on the second floor from 1888 until 1893. Here we wrote ‘Missa in festo’ in 1891. (2018)

Year 1888. Former Gymnasium in Den Bosch where Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) was teacher Latin and Greek from 1888 until 1893. (2018)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) and Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939)

On 19-10-1903, Year 1903, Gustav Mahler came to Amsterdam to conduct his Third and First Symphony. Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) introduced him to Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921). Immediately the two composers – age difference two years – felt attracted to each other. Mahler wrote enthusiastically to his wife Alma Mahler (1879-1964):

“I met a very interesting Dutch musician, Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921), who writes very peculiar church music. The musical culture in this country is stupendous.”

Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) shared in their friendship. At every dinner gustav Mahler wanted to have the couple Diepenbrock next to him, then he enjoyed himself the best.

Alphons guided the Austrian through the city. Mahler was almost a head shorter than Fons (Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921)), he walked bare-headed in an unpredictable cadence. Sometimes he stayed behind, then he shot back vaguely. Street boys shouted after him: Sir where is your hat?

At the Damrak, Mahler remained an admiring steamer for the brand new Beurs van Berlage. When Fons told him that this was a stock exchange building, which he did not like at all, Mahler said with unwavering admiration: “A fair, where greed rules, may not look like a temple!”. He asked about the name of the architect and said to Fons: “Tell him he is a great architect.” He himself was a supporter of the Wiener Secession. In a letter to Alma he mocked the exuberant neo-gothic home furnishings of the Mengelbergs, with whom he stayed in the Van Eeghenstraat (see House Willem Mengelberg).

When he returned home, Mahler wrote that he had “liebgewonnen” for Diepenbrock.

Fons had given him the favorable Dutch reviews; Mahler did not consider the hostile reactions, he was used to them. He had found the purity of the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO) wonderful and he was at home. A world had also opened up for Fons:

“Mahler is very simple, poses not for celebrity, gives himself as he is. I have the greatest admiration for him. [..] Bon enfant, naive, sometimes childish, behind a large crystal glasses he kicks with sp He is modern in every way. He believes in the future. How should I feel like a grieving ‘Romantiker’. I can tell you that his presence did me good”.

Mahler had taken away his doom-image that modernity irrevocably went hand in hand with democracy and populism. The Viennese composer did not meet people in their weakness, but lifted them higher with his genius.

His music could change the audience and give a catharsis. Fons called him the Beethoven of his time.

From the second visit of Mahler to Amsterdam, a year later, Year 1904, Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) claimed to capture every moment in her diary. Immediately after his arrival, Fons took him home to play his Te Deum. He now called his friend Gustav. “Mahler loves Fons”, wrote Elsa. “Always wants him everywhere. “

When Mahler had to go to a compulsory dinner without the Diepenbrocks, he sighed: “What should I do if my friends are not there?” For the premiere of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, which was shortly proclaimed as a scandal in Germany, Mengelberg wanted to take no risk, 1904 Concert Amsterdam 23-10-1904 – Symphony No. 4 (twice), he placed this symphony twice on the poster, before and after a break. Mahler thought it was a long time to get used to his idiom, he conducted both grinder himself.

The double concert ended in an ovation, with which the public also expressed his admiration for the exceptional physical performance of the conductor. Most beautiful music, Elsa wrote in her diary. Mahler did not want Fons and Elsa to go home after supper that night.

“We still had to stay. Mahler then says wonderful things about the essence of music, it was an unforgettable moment and Fons animated him every time, so that he came into full fire. Fons calls him Orfeus, and says that he has an antique view of music”.

The Second Symphony premiered on 1904 Concert Amsterdam 26-10-1904 – Symphony No. 2. During the dress rehearsal, Elsa sat with Fons and Mengelberg in the empty hall of the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw.

Seeing conducting, he gives everything and is of a liveliness of movement that is amazing. “So Beethoven must also have directed,” Fons said.

To relax before the concert, Mahler went to eat at House Diepenbrock with the Mengelbergs. Completely at home, he talked out loud about his birthplace, which did not have any unbroken windows, and about his younger brothers, the earthworms, and he would like to have four children, but not a quad, because he liked variety.

That evening, With the wonderful final choir, Auferstehn, noted Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) “Fons told him in 1904 Hotel American, that he liked to use existing motifs and melodies in his compositions, because all music is connected to earlier: only an or the composer came up with something new or personal about it. Of course, ‘Mahler replied, grabbing Fons’ hand, that is not a sheep and not an ox, that is nothing but Diepenbrock!

The next day Fons wanted to show Mahler his holiday home Villa De Hoeve, with the modern art collection. Willem Mengelberg walked from Hilversum over the heath to Laren. Elsa and Mathilde Mengelberg-Wubbe (1875-1943) (Tilly) took them to lunch together at Saar and Emilie (see Saar de Swart (1861-1951)). At the table Mahler was very fascinating about the content of his Second Symphony, wrote Elsa, without going into details.

For Elsa, Mahler’s stay meant “beautiful festive days, as filled by the enchanting personality as by the wonderful music and the warm relationship”. She reflected on Mahler’s appreciation for her husband’s compositions, and he eagerly wanted to have the Te Deum performed in Vienna, and he liked all of his songs beautifully, she wrote, especially “Hinüber wall ich” on a poem by Novalis.

Fons made a piano extract of the last parts of the Fourth Symphony to be able to play this music themselves, and inspired him for his symphonic song “Im grossen Schweigen” which he composed shortly afterwards on a text by Friedrich Nietzsche.

Mahler also felt stimulated in his creativity by the admiration of Mengelberg and Diepenbrock: It was the very first time that he received support from eminent foreign musicians.

Year 1908. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) – Auf dem See (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832))

More on Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921)

- 04-06-1893 Alphons visited House Annastate in Den Bosch for the first time, where he met his future wife Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) lived. He played music by Richard Wagner (1813-1883) there. Else admired Wagner. Diepenbrock hesitated about a marriage proposal. The combination of being a teacher and the ambition as an artist played a role. In that case Elsa would be subordinate to the artist who gets all the attention. The perverse enjoyment of the melancholy of Alphons played also a role.

- The husband of Elsa’s sister (Cecile, Paul Goekoop) was very prosperous and offered to help financially if necessary (was the case).

- 12-1893 Wedding proposal. Alphons was from a Catholic family. Else was Protestant.

- Alphons was less concerned with feminism than Else and had a weak health.

- 1895: It took one and a half years to try to have a mixed marriage with a church blessing.

- Alphons stopped his work as a school teacher.

- 1897: Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) had supported the beginning composer from the start.

- Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) and Mathilde Mengelberg-Wubbe (1875-1943) visited Alphons and Else regularly.

- 1904-1919 Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) had a lover: Johanna Jongkindt (1882-1945). Triangle relationship. Diepenbrock gave her a copy of Des Knaben Wunderhorn he had bought when he was a student. When Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) and Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) visited the Frans Hals Museum (24-10-1904) Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) sent his lover Johanna Jongkindt (1882-1945) a postcard with signatures by all three man.

- 08-03-1906: See Zuiderzee and House Diepenbrock. With Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951).

- 1911: Carl Julius Rudolf Moll (1861-1945) informed Diepenbrock by letter about Mahlers very weak condition.

- 1911: Attended Gustav Mahler funeral.

- 00-04-1912 Frankfurt: Symphony No 4 by the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO). Also Te Deum by Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921). First time Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) and Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) meet Alma Mahler (1879-1964), who never came to the Netherlands with her husband.

- 1913: First meeting Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) in Amsterdam. Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) visited House Diepenbrock often.

Alphonsus Johannes Maria Diepenbrock was a Dutch composer, essayist and classicist. Diepenbrock was not a musician by training. Influenced by Wagner but with his own idiom. Brought up in a prosperous Catholic family, although he showed musical ability as a child, the expectation was that he would enter a university rather than a conservatory. And so he studied classics at the University of Amsterdam, gaining his doctorate cum laude in 1888 with a dissertation in Latin on the life of Seneca. The same year he became a teacher in Latin at the urban gymnasium in Den Bosch, a job which he held until 1894, and his decision to devote himself to music. He made an ethereal and tormented impression on his fellow citizens at the time.

Year 1906. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) and Joanna (1905-1966). 18-07-1906.

Year 1907. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) with Joanna.

Year 1908. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) and Joanna.

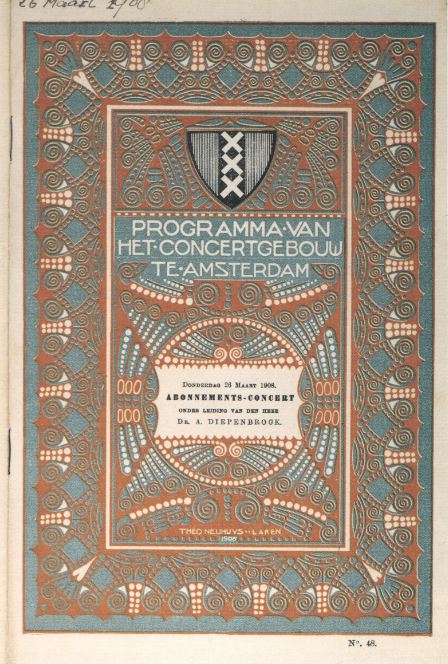

Year 1908. Program 26-03-1908. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Symphony No. 4 and Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) Hymne to Rembrandt (composition 1906). Conductor Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921). Design program Theo Neuhuys, 1906.

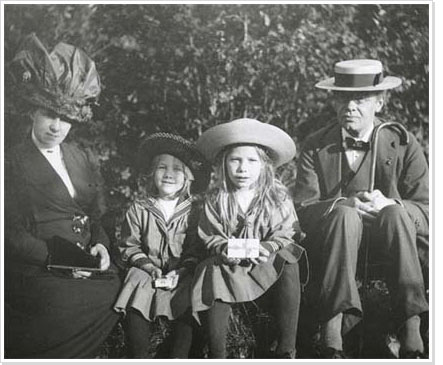

Year 1909. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) with Joanna and Thea.

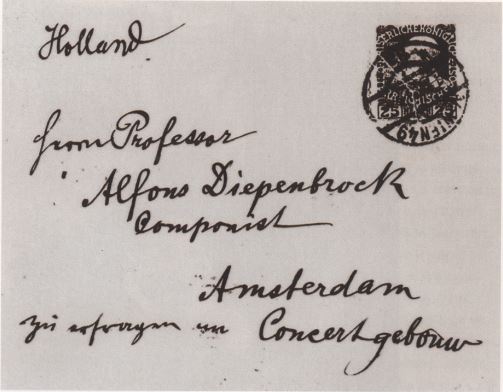

Letter from Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) to Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921), Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam.

He created a musical idiom which, in a highly personal manner, combined 16th-century polyphony with Wagnerian chromaticism, to which in later years was added the impressionistic refinement that he encountered in Debussy’s music. His predominantly vocal output is distinguished by the high quality of the texts used. Apart from the Ancient Greek dramatists and Latin liturgy, he was inspired by, among others, Goethe, Novalis, Vondel, Brentano, Hölderlin, Heine, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Baudelaire and Verlaine.

As a conductor, he performed many contemporary works, including Gustav Mahler’s Fourth Symphony (at the Concertgebouw) as well as works by Fauré and Debussy.

Throughout his life, Diepenbrock continued his interests in the wider cultural sphere, remaining a classics tutor and publishing works on literature, painting, politics, philosophy and religion. Indeed during his lifetime his musical skills were often overlooked. Nonetheless, Diepenbrock was very much a respected figure within musical circles. He counted amongst his friends Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), Richard Strauss (1864-1949) and Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951).

Some of his works:

- Missa in die festo (1891).

- Stabat Mater Dolorosa (1896)

- Te Deum (1897).

- Hymne for violin and piano (1898). Orchestrated. First performance 1899.

- Ik ben in eenzaamheid niet meer alleen (1898).

- Hymne an die Nacht (1899).

- Vondels vaart naar Agrippine (1903).

- Im Grossen Schweigen (1906).

- Hymne to Rembrandt (1906). For soprano, female chorus and orchestra.

- Auf dem See (1908).

- Die Nacht (1911).

- Marsyas (1910).

- Gijsbreght van Aemstel (1912).

- De Vogels (1917).

- Elektra (1920).

Year 1910. July. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) and Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) with Joanna and Thea.

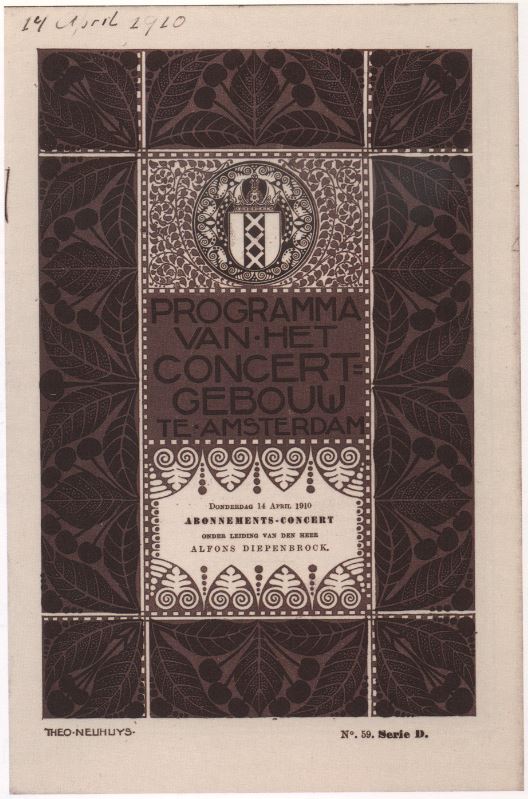

Year 1910. 14-04-1910 Program Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) performance Symphony No. 4. Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO), Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw.

Year 1910. 14-04-1910 Program Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) performance Symphony No. 4. Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO), Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw.

Year 1911. 22-05-1911. Postcard Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) to Balthazar Huibrecht Verhagen (1881-1950) (in the Hague): ‘On the day of the funeral of Gustaaf Mahler I send my friend Balthazar a melancholy greeting’. On the front Diepenbrock wrote the funeral theme from the first part of Gustaf Mahler’s Symphony No. 5. Postcard Grand Hotel Vienne, I, Kartnerring No. 9, Vienna. See also Diepenbrock at: Gustav Mahler funeral.

Year 1911. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) with his wife Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) and their daughters Thea (1907-1995) and Joanna (1905-1966). Bredius forest, Laren, The Netherlands. Photo by his friend Gijs Hondius van den Broek (1867-1913).

Year 1911. Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) and Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) with Joanna and Thea. House Holtwick, Laren, the Netherlands.

- Diepenbrock gave clues to the musicians who would perform his work with time-consuming perfectionism.

- Mariencomplex. Like Gustav Mahler.

- 1908: 71 kg, 1.77 meters.

- Gijs Hondius van den Broek was a friend of both Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) and Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939).

More

Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921)

Born in Amsterdam, Alphons Diepenbrock descended on his father’s side from an ancient Roman Catholic Westphalian family. The Diepenbrock castle still exists and can be found slightly north of Bocholt, close to the Dutch border. His mother, Johanna Kuytenbrouwer, descended from a family from Amsterdam. The very pious Diepenbrock family was in contact with the leaders of the Dutch Roman Catholic revival.

When he was young Diepenbrock proved to be musical but he never received a proper music education. He taught himself to play on a beautiful Erard grand piano, had some lessons, and, at the age of 18, went to the University of Amsterdam to study classical languages. He graduated cum laude with a dissertation on Seneca. During his student years he became involved in the “Beweging van Tachtig”. For his career, Diepenbrock took practically no lessons – excepting some instruction by Bernard Zweers (1854-1924).

He studied Bach’s Wolhltemperierte Klavier soon followed by Wagner’s Tannhäuser, Rheingold and Tristan und Isolde. For some time Diepenbrock considered going to Vienna to take lessons in composing from Anton Bruckner, a composer who at that time was hardly known at all in the Netherlands (or in the rest of Europe).

In Diepenbrock’s compositions, almost all of which are vocal works, he strove to find a synthesis of Wagner’s chromatic language and the polyphonic world of both Palestrina and Bach. Being a classicist himself, he payed a lot of attention to the (free) rhythm of the texts.

The first work to show Diepenbrock’s genius is the eleborate Missa in die festo for tenor, 8-part male choir and organ, which was printed in 1895. It was an almost impossible task to write a very modern work in combination with the religious naivety of composers like Palestrina and Bach. As such a fervent admirer of Nietzsche wrote a work in which he, almost tragically, struggled with his profound religious conscience and the equally profound notion that in the intellectual Europe religion had become an idle game. In this aspect he deeply resembles a composer like Gustav Mahler (1860-1911).

Diepenbrock’s music is nearly allways polyphonic, poly-melodic. Just like Wagner’s compositions (and like the plain chant that was so important to Diepenbrock), the melody is free from strict meter, the music breathes along with the text. In the poly-melodic aspect of his music – which is also found in the work of two other Dutch composers: Matthijs Vermeulen (1888-1967) and Rudolf Escher (1912-1980) – we hear the echoes of composers like Josquin and Ockeghem.

At first Diepenbrock’s contacts in the world of art were mostly literary.The only professional composer with whom he was in correspondance wasthe Dutch-Belgian composer Carl Smulders (1863-1934), who lectured at the University of Liège. For several years Diepenbrock befriended the Hungarian composer Emanuel Moór (1863-1931).

In the meantime Diepenbrock gradually began to dislike the extremel ’art-pour-l’art of the “Beweging van Tachtig” (and Wagner!). He tried to find – still deeply imbedded in Roman Catholicism – music that wasn’t too individual. Typical in this aspect is Diepenbrock’s (still very Wagnerian) arrangement of Nietzsche’s Im grossen Schweigen (Morgenröthe) from 1906. When the philosopher laments over the speechlessness of nature and the silence of mankind, Diepenbrock quotes the hymn Ave Mariastella as an answer to the questions the philosopher asks.

He became increasingly interested in the clear Latin world of composersl ike Debussy. And he gradually renounced the music of Wagner and Richard Strauss. A definite choice in favour of French music (which proved to be of great influence on Dutch music) was prompted by the first World War. Diepenbrock opposed the Prussian-German expansion in fierce articles and compositions. The Dutch composer (and Diepenbrock’s adept) Willem Pijper (1894-1947) wrote: “In this context it is worth noticing that one spokewith be littlement of ‘war neurosis’ and ‘Germanophobia’. It may be useful to correct this view.

In 1912, when nobody here thought about the bombardment of Rheims or the ‘rücksichtslose’ submarine war, Diepenbrock already composed his Berceuse on a text by Van Lerberghe, a short workwhich is as French as can be. It is so very French that it proved to be one of his lesser works. His first songs on words by Verlaine date back to 1898. In 1892 he wrote his famous study on De Gourmont’s ‘Le latin mystique’. His love for French literature and music meant much more then just a reaction to the matters occuring in the world; his almost prophetical enrapture was a reaction to his own yesterday that had died.”

His interest in a composer like Debussy of course was evident in his own compositions, such as in his music for the play Marsyas by Balthazar Verhagen (1910).

Strangely enough his sympathy for French music didn’t lead to many friendly contacts. His meeting with Debussy (who was by then fatally ill) was astraightforward disappointment. His only true friend was Gustav Mahler. His sympathy for the music of Strauss and Schoenberg proved to be temporary.

Diepenbrock and Mahler became friends when Mahler conducted the Concertgebouw orchestra as they played his Symphony No. 3 (1903 Concert Amsterdam 22-10-1903 – Symphony No. 3). As is known, Mahler in this work combines a text by Nietzsche (Zarathustras Mitter nachtslied) with a text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (“Es sungen drei Engel”). Diepenbrock, an authority on both Nietzsche and the world of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, was at first surprised by this grotesque combination oftexts. But soon afterwards he became familiar with both Mahler and his work.

On 21-10-1903 Mahler wrote from the Dutch city Zaandam to his wife (Year 1903):

“…Gestern die Generalprobe war herrlich. Zweihundert Jungen aus der Schule unter Begleitung ihrer Lehrer (6 Stück) brüllen das Bim-Bam und ein famoser Frauenchor von 330 Stimmen! Orchester herrlich! Viel besser als in Crefeld. Die Violinen ebenso schön wie in Wien. Alle Mitwirkenden hören nicht auf zu applaudiren und zu winken. Dass du nicht dabeisein kannst! […] Einen sehr interessanten holländischen Musiker, namens Diepenbrock, der sehr eigenartige Kirchenmusik schreibt, habe ich hierkennen gelernt. -Die musikalische Kultur in diesem Lande ist stupend. Wie die Leute bloss zuhören können!

And Diepenbrock wrote to a friend in an elaborate letter:

“…I met Gustav Mahler last week. This man impressed me very much indeed. I’ve heard and admired his Third Symphony. The first movement contains a lot of ugliness, but, after listening to it a second and third time and knowing what it means to say, it already seems to be different. Mahler is a very simple man, he doesn’t pose himself as a celebrity, he is just as he is. I admire him very much… Bon enfant, naive, sometimes a little bit childish,he looks through large crystelline glasses with magic-filled eyes. In every aspect he is modern. He believes in the future.”

Mahler’s first visit to the Netherlands was an immediate success. A success also made possible by Willem Mengelberg who had rehearsed the Concertgebouworchestra with a high degree of accuracy. On October 30, 1903 a very grateful Mahler wrote him a letter from Vienna:

“Lieber und werter Freund! An bei, wie versprochen, ein Schock von uns ‘eingerichteter’ Partituren. Lassen Sie mich Ihnen bei dieser Gelegenheit nochmals sagen, wie wohl mir die schönen Tage gethan, die ich in Ihrer und Ihrer lieben Frau Gesellschaft verlebt, und das ich das Gefühl habe, das mir in Amsterdam eine zweite Heimath erstanden ist, dank Ihrer freundschaftlichen Fürsorge und Ihres so innigen künstlerischen Verständnisses. Nochmals herzlichsten, treuesten Dank für alles. Ihr stets verbundener Gustav Mahler.

Diepenbrock, den ich auch herzlich liebgewonnen, grüssen Sie vielmals von mir. Bei Gelegenheit antworte ich auf seinen sehr lieben Brief, den ich in der Bilderrolle erst nach meiner Ankunft in Wien aufgefunden.”

Mahler was to stay several times in the Netherlands. A year later already, 19-10-1904, Year 1904, he was in Amsterdam again. The day before Diepenbrock’s Te Deum was performed in Strassburg without Diepenbroc kbeing there. Diepenbrock’s wife Elisabeth wrote in her diary on 20-10-1904:

“Mahler is again in the city. Fons will pay him avisit today, there’s a lot of warmth between them; they will take a walk through the city after which Fons will play his Te Deum. Mahler is enthusiastic and wants to perform it in Vienna.”

On 23-10-1904 Mahler conducted a programme that became famous: his Fourth Symhony was played twice. 1904 Concert Amsterdam 23-10-1904 – Symphony No. 4 (twice) Mahler wrote to his wife (Year 1904):

“Liebste! Das war ein erstaunlicher Abend! Das Publikum ist von Anfang an so aufmerksam und verständig gewesen und war von Satz zu Satz wärmer. – Das zweite Mal wuchs die Begeisterung, und nach dem Schluss gab es etwas ähnliches wie in Crefeld. Die Sängerin hat das Solo mitschlichtem und rührendem Ausdruck gesungen und das Orchester hat sie begleitet wie Sonnenstrahlen. Es war ein Bild auf Goldgrund. Ich glaube nun wirklich, dass ich in Amsterdam jene musikalische Heimat finde, die ich mir in diesem vertrottelten Köln erhofft habe. – Heute geht es an die Hauptproben zur Zweiten. Das giebt noch eine harte Nuss. Das Orchester ist hier wieder reizend zu mir! Ich küsse Dich vielmals, mein Almschi.”

See also: Gustav Mahler himself in the Netherlands (1903, 1904, 1906, 1909 and 1910).

“… After the concert supper at Mengelberg’s, and when everybody had left, Mahler didn’t want Fons to leave (they were sitting close together), we had to stay. Mahler then said wonderful things about the essence of music, it was a moment never to be forgotten in which Fons encouraged him again and again so that he was all in flame. Fons calls him Orfeo and tells him that he has a classical opinion of music.”

A day later Mahler, Diepenbrock and Willem Mengelberg together payed a visit to the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem. Unfortunately they arrived too late so that two days later Mahler ended an afternoon rehearsal earlier than usual in order to visit the museum.

On 27-10-1904 Mahler, Diepenbrock and Mengelberg walked from Hilversum to Laren.

Elisabeth wrote:

“Mathilde Mengelberg-Wubbe (1875-1943) and I will go later, we will catch up with them. Mahler often walks in front alone, without a hat, silent, he sometimes returns and talks, he is delighted with the country, the village, (…), and at dinner compellingly tells about the contents of the Second Symphony. Then we walked back and listened to the repeated Second that evening.”

Another nice comment on Mahler: Mahler – being used to the sober Wiener Secession – absolutely didn’t feel at home in Mengelberg’s overdecorated Neo Gothic home – Mengelberg’s father was the owner of arenowned studio of Neo Gothic church decorations. At a certain moment Mahler is said to have exclaimed: “Das Geschwätz des Vaters hängt beidem Sohn an der Wand!”

When Diepenbrock proclaimed that Berlage’s Beurs (the stockexchange) wasn’t to his liking Mahler said he found Berlage a great architect.

In 03-1906 Mahler, Year 1906, visited the Netherlands for the third time conducting several concerts of his Fifth Symphony, the Kindertotenliederand Das klagende Lied. See Gustav Mahler himself in the Netherlands (1903, 1904, 1906, 1909 and 1910).

On 25-10-1908 Diepenbrock conducted the Concertgebouw orchestra in a concert of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Diepenbrock wrote a programme note on Mahler’s work for the occasion.

For various reasons, amongst others conducting in the USA, Mahler returned to the Netherlands as late as 1909, Year 1909.

On 27-09-1909 Mahler was in Amsterdam again to conduct his Seventh Symphony. Mahler wrote to his wife on 29-09-1909: “…Diepenbrock fand sich auch schon zur ersten Probe ein. Das ist so ein prachtvoller Kerl…”

Except for a visit that he kept secret from his friends in Amsterdam – he payed a very short visit to Leiden to consult Siegmund Freud on his psychical and sexual problems in his marriage with Alma – this was to be the last visit of Mahler to the Netherlands.

For the last time, on 14-04-1910 Diepenbrock conducted Mahler’s Fourth Symphony (which to him was the most beautiful), this time with Aaltje Noordewier-Reddingius (1868-1949) as a soloist.

On 18-05-1911 Mahler died. Even though Diepenbrock had been warned in a letter by Carl Julius Rudolf Moll (1861-1945), Mahler’s death came as a severe blow. It was evident to him that he had to be present at Mahler’s funeral. As anofficial delegate of the “Maatschappij tot bevordering der Toonkunst” he placed a funeral wreath.

Elisabeth Diepenbrock wrote in her diary on 07-06-1911:

“A lot of memories welled up. How he came to us for the first time to see Joannetje lying in her crib and how he watched the tiny lovely thing with warm tenderness. Later on he remarked on her and the last time I saw him with the little ones on the street he suddenly stood still and said: ‘Ach, gnädige Frau, ich erkenne Sie an den Kleinen.’”

Mahler’s funeral impressed Diepenbrock so much that he left Vienna immediately after the ceremony even though he had never been in Vienna before.

On 28-11-1912 Arnold Schoenberg conducted his Symphonic Poem Pelleas und Melisande op. 5, that he wrote in 1902/1903, in the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. Schoenberg was in the Netherlands on an invitation by Willem Mengelberg.

Diepenbrock and his wife Elisabeth went to both the rehearsal and tothe concert. Elisabeth wrote in her diary:

“… After that we met Arnold Schoenberg. He conducted on 28-11-1912 his Pelleas et Melisande, that was composed at the same time as Debussy’s work which he admired very much, and of which he said: Dass ist die wahre Musik zum Pelleas, because he himself expressed his self more than the poetical text.

So very many bad things are told and written about him like: the destroyer of all musical tradition, but we rather liked him. He is a nice and witty fellow, agile but not fatiguing, flexible and modest.

We were at the rehearsal in the morning and his wife was there too, and we asked them to visit us that evening for an hour or so. They were pleased to do so and we also invited Cornelis Dopper and Louis Zimmermann. I was in a very good mood and we talked about Gustav Mahler, an acquaintance of Schoenberg’s whom he admired very much indeed. When Fons asked him whether or not he’d met Mahler, Schoenberg answered: Er liess uns zu, to express his admiration and his own position in the presence of the Master.

We found the Pelleas much too long and too heavy, too German in sound, but with a lot of beauty and very real, not like the work Scriabin makes. It shows a real personality. On Friday afternoon Fons took him and his wife to see the collection of Drucker, and Schoenberg was raptured by the work of Maris (even though he makes cubistic paintings himself), and later on we met each other accidentally at the Japanese auction, where I was with the little ones and we had tea together at Ledeboer.

In the evening they cameover to tea and Fons played his Marsyas (fragments) and Te Deum on Schoenberg’s request. He especially liked the Te Deum and he immediately wrote to his friend Franz Schreker (1878-1934) in Vienna, who had asked for a copy of it. On Saturday we saw them home to the train; he went to The Hague to conduct Pelleas and we warmly departed, and they said their visit to Amsterdam had been very pleasant thanks to us and that we were the only ones that took notice of them.”

Schoenberg immediately wrote to Diepenbrock on 07-12-1912:

“…Verehrter Herr Diepenbrock, beiliegende Karte von Schreker Ihnen zu senden, macht mir grosses Vergnügen. Ich glaube, dass Schreker un bedingt Wort hält. Jedenfalls wird es gut sein, wenn Sie ihm das entsprechende Material gleich schicken, ehe er fürs nächste Jahr Programmmacht. – Ich will Ihnen bei dieser Gelegenheit (Ihnen und Ihrer Frau!) nochmals auch namens meiner Frau aufs herzlichste danken für Ihre Gastfreundschaft. Und hoffentlich haben wir bald in Berlin Gelegenheit, sie zu erwidern. Mit den herzlichsten Grüssen Ihr Arnold Schoenberg.”

The answer of Diepenbrock, Amsterdam, 13-12-1912:

“Verehrter Herr Schoenberg, Besten Dank für Ihren Brief und die Empfehlung an Schreker. – Morgen gehn Klavier Ausz. und Partitur nach Wien. Die Zusage S’s an Ihnen [sic] genügte mir um Herrn S. die selben zusenden. Nach Kenntnisnahme steht es ihm selbstverständlich frei wenn das Werk Ihm aus irgend einem Grunde nicht passt, auf die Aufführung zuverzichten.

Uns war es eine Ehre und Freude Ihre und Ihrer liebe Frau Bekanntschaft zu machen, und wenn wir Ihnen beiden den Aufenthalt inirgend einer Weise angenehm gemacht haben, freut uns das doppelt. – Im Ganzen können Sie mit der Kritik zufrieden sein, wie mir scheint. Ich habe Einiges bewahrt und werde es Ihnen schicken. Vielleicht kennen Sie in Berlin einen der vielen dort ansässigen Holländer, der sie Ihnen übersetzenkann. – Erlauben Sie mir eine Bitte. – Mein Copist ist der Musiker der in dem Orchester das Englische Horn bläst. Er sagte mir Sie seien mit ihm zufrieden gewesen, und er hätte Ihnen gerne ein Zeugniss fragen wollen, aber nicht den Muth dazu gehabt. Er möchte bloss zu seinem Vergnügendieses Zeugniss haben, nicht um damit etwa sich um eine andere Stelle zubewerben. – Wenn Sie also über ihn zufrieden sind, machen Sie ihm die Freude. Er ist ein armer Kerl, der sich schwer plagen muss. Ohne Ihre Zustimmung wird er sich auch gewiss nie dieses Zeugnisses bedienen. Nameund Adresse sind W. Tiel (TIEL) Hobbemakade 169 (near House Diepenbrock). – Leben Sie wohl, undkommen Sie zurück!”

Schoenberg immediately provided what he was asked for and wished to be informed about the Te Deum, Berlin, 30-12-1912

”Sehr geehrter Herr Diepenbrock, verzeihen Sie, dass ich Ihnen so spät erst antworte. Ich war in St Petersburg, Pelleas aufzuführen und fand bei der Rückkehr viel dringende Arbeit vor. – Ich sende Ihnen beiliegend den Brief für Herrn Thiel. Es ist mir höchst angenehm, ihm ein Vergnügen zumachen. Wenn Sie glauben, dass es so recht ist, bitte ich Sie es ihm zugeben. – Gerne wüsste ich, wie Sie mit Schreker stehen. Hat er sich schon geäussert? – Ich bitte Sie, Ihre Frau Gemahlin herzlichst von meiner Frauund mir zu grüssen. Ebensolche Grüsse auch an Sie, und Prosit Neujahr! IhrArnold Schoenberg.”

Schoenberg soon received a typical Diepenbrock letter, Amsterdam, 08-011913:

“Verehrter Herr, Besten Dank für Ihren Brief auch von Tiel der ganzentzückt war. Ich danke Ihnen auch noch dass Sie die Güte hatten, meiner Bitte Folge zu leisten. – Leider habe ich von Herrn Schreker nichts gehört, obwohl ich ihm zugleich bei der Übersendung der Partitur und des Kl. Ausz. gebeten habe mir die gute Ankunft auf einer Karte mit ein Paar Worte [sic] zu melden. Ich vermuthe jedoch dass Ihr Freund falls ihm die Musikaliennicht erreicht hŠtten, mir davon Kunde gegeben hätte.

Übrigens habe ich inmeinem Leben – und ich bin leider schon 50 – schon so viele schlechte Erfahrungen in dieser Hinsicht gemacht, dass ich gelassen undunempfindlich geworden bin. Dies selbe Te Deum was ihm Gustav Mahler empfohlen hatte und um dessen Übersendung Herr Schalk in Wien mir bat, hat derselbe Schalk, weil es seinem Chor nicht lag, unfrankirt [sic] zurückgesandt.

Mahler war darüber entrüstet. Grämen Sie sich nicht über Herrn Schreker wenn er nicht antwortet. Ich habe ihm geschrieben er hättesich zu gar nichts verpflichtet. Wenn das Werk ihm aus irgend einem Grunde (subjectif oder objectif) nicht tauge, könne er die Musikalien zurückschicken. Das verstehe ich ja sehr gut, dass eine Arbeit einem nicht zusagtund dem anderen gefällt, oder auch in Hinsicht des Publikums oder der technischen Schwierigkeit etc. nicht passt. Aber man kann immer eine Kistefrankiren aus Respect – für einen Gustav Mahler, man kann auch eine Karteschreiben. Ich bin aber deshalb dem Herrn Schreker nicht böse. Es ist das Los der ‘unberümten’. Werde ich jemals diese Linie überschreiten, und michin den Gefilden der Seligen mit den Heroen herumtummeln? Wer weiss es? -Leben Sie wohl, lieber Herr Schoenberg. Ich wünsche Ihnen und Ihrer Frau Gemahlin alles Schöne und Gute im neuen Jahre 1913. Auf Wiedersehen. Ihr ergebener A. Diepenbrock.”

In the letter from Schoenberg to Diepenbrock of 23-06-1913 we read for the first time of his plans to produce the gigantic Gurrelieder in Amsterdam:

“Verehrter Herr Dr. Diepenbrock, Sie waren so freundlich mir zum Mahler-Preis zu gratulieren und ich musste (da durch meine Uebersiedlungmeine ganze Zeit mit Beschlag belegt war) so unartig sein, Ihnen nicht sofort zu antworten. Seien Sie mir nicht böse deshalb und nehmen Sie jetztnoch meinen umso herzlicheren Dank für Ihre Liebenswürdigkeit. -Ich freuemich dass ich Sie und Ihre Frau Gemahlin im nächsten Jahr wieder sehenwerde. Denn ich dirigiere im Februar meine Orchesterstücke in Amsterdam. Vielleicht auch die Gurrelieder (im Dezember). – Mir geht es sonst im Ganzen gut. Auch meiner Frau. Wie geht es den Ihrigen? – Kommen Sie nichteinmal nach Berlin? Viele herzlichste Grüsse, Ihr Arnold Schoenberg.”

In March 1914 Schoenberg was in Amsterdam again to conduct his Fünf Orchesterstücke Op. 16, splendid music but still too complicated for most people. (Richard Strauss described it as “inhaltlich und klänglich […] gewagte Experimente” and never conducted it… Especially the third part (Farben) with the very subtle tone changes was too much for most people.

Schoenberg to Diepenbrock, Amsterdam, Hotel-Pension Boston, 09-03-1914:

“Verehrter Herr Dr. Diepenbrock, ich bin – für mich ‘unerwartet’ -bereits gestern abends hier angekommen und probiere heute morgens schon.- Wann kann ich Sie sehen? – Ich bin mit drei Freunden (Anton Webern (1883-1945), Alban Berg (1885-1935) and Erwin Stein) hier und möchte gleich nach dem‘Lunch’ ins Reichsmuseum gehen. – Kann ich Sie dann um 4 Uhr irgendwo treffen? …”

The next day (10-03-1914) Diepenbrock was at the rehearsal of the Fünf Orchesterstücke. In the afternoon Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) payed Diepenbrock a visit a this house in the Verhulststraat(House Diepenbrock), and left Anton Webern (1883-1945) and Alban Berg (1885-1935) to wait outside in the pouring rain as they were but students at the time! In an in memoriam article after Schoenberg’s death, which appeared in De Groene Amsterdammer of 08-09-1921, the composer Matthijs Vermeulen (1888-1967) remembers:

”When I went to visit Diepenbrock […] I met at his door two young men shorter and darker, both of them probably 25 years old in a rather akward position. In the hall near the staircase Schoenberg walked by and I, a newcomer myself, and having no right to his attention, saluted him. Upstairs, in his working room, Diepenbrock reached me his hand and asked me, both satirical and emotional: Did you see him, the master and his pupils? Then I heard that the two young men that I had met as an outsider at the entrance already had their legend. They followed their master everywhere. But not being inaugurated themselves, they had to stay outside when masters met each other. To Schoenberg this was a matter of course and to them it was just their duty to pay such a respect…”

Diepenbrock wrote to Johanna Jongkindt (1882-1945) on 11-03-1914:

“At the moment the prince of Kakaphonikers is here, a certain Schoenberg (Arnold) a Jewish fellow from Vienna now residing in Berlin: he looks Japanese with a round, yellow and bald head, circa 40 years old, an extraordinarily gifted musician, but lacking – in my opinion – every sense of beauty. I was at the rehearsal yesterday but I didn’t go today. It’s as if everyone is playing what’s entering his head at that moment, a continuous series of terrible sounds, a cacophony. I can’t imagine anyone else who –although seeming to be an honest person and an absolutely naive artist, if possible even more so than Mahler, and possessing an absolutely unbelievable musical talent, as is proved by his earlier compositions – could produce such ugliness.”

In 04-1914 Mengelberg wrote to Schoenberg of his intention to perform the Gurrelieder. Schoenberg was to conduct the rehearsals himself. The First World War precluded this. In 1920 Schoenberg went back to Amsterdam where he conducted his Verklärte Nacht and Vergangenes from the Fünf Orchesterstücke op. 16 (the other parts couldn’t be performed due to his late arrival in Amsterdam).

There was never to be any further contact between Diepenbrock and Schoenberg. The Gurre lieder were performed in Amsterdam in 1921, when Diepenbrock, the author of the wonderful stage music to Sophocles’ Electra and the almost forgotten music to Goethe’s Faust, was already on his deathbed.